Dolly’s House

13 May 2011

Shrouded in fog the Roslin Institute, home of Dolly the Sheep, cuts an ominous presence in the wan light. “I wish it was a bright and sunny day because the building really shines” laments Bea Sennewald, project director at HDR, as she ushers a delegation of invited guests, Urban Realm amongst them, to peruse the American practice’s latest UK completion. The empty corridors and vacant spaces suggests the buildings occupants have vanished into the swirling mists but clocking the seats still in the wrappers and the sweetly aroma that accompanies a new building it becomes apparent that this seat of science hasn’t fallen to the supernatural, it merely awaits its first tenants.

Occupying an area of former farm steadings on the University of Edinburgh’s Easter Bush campus, the development saw demolition of what amounted to little more than garden sheds along with the refurbishment of more substantial stables into a electrical substation. The first phase of a much larger development it will see a campus of shoddy neighbouring 1950s buildings swept away in a rolling programme of estates development that is intended to draw leading international talent to the city.

“Our first design idea was based on the study of a chromosome,” explains Sennewald, translating the coiled strands of DNA into an “office zone, lab zone and connectors comprising social and interactive zones. Not corridors,” stresses Sennewald, “these are functional spaces intended not just for circulation but to make the building more efficient but also means people talk and bump into each other as a social space. As circulation is through places that people meet and gather people are more likely to meet others outwith their team or lab.”

Piercing the leaden grey fronds of water vapour inside is a dazzling rainbow of colour which dances across the central spine of the Institute in reference to the spectrum of light from infrared to ultraviolet. “The colours are purposeful,” emphasises Rachel Park, HDRs strategic facilities planner, “not just what was on offer at the paint sale.” This emphasis on colour stands in marced contrast to the dim light outside as Sennewald observed: “You never know if the light will be pink or green” Fortuitously the mists begin to clear and something of the play of photons to which Sennewald alludes becomes apparent.

Started in April 2007 and moved in March 2011 in probably one of the coldest winters Scotland has seen. Sennewald was thus fortunate to observe the construction process on webcam but found herself donning wellies soon enough when a site visit was called for. “How do you create a building that can be used by different organisations in the future?” asked Sennewald. HDR came with three design ideas. Eschew a furniture solution for how the spaces are made, maximise the spread of light and minimise individual office space in favour of collaborative spaces. Rachel added: “Workspace is changing; it’s no longer cellular, stuffy, becoming much more nimble, allowing people to collaborate and interact. Concerns about acoustic privacy and distractions abounded however, particularly subtle changes in behaviour effected by the changed working environment. A new found respect is needed between workforces who must observe the needs of their colleagues by retiring to designated break out spaces for discussion and sharing desk space with others. “The secret to a building’s success is if you can reduce the anxiety of change,” adds Sennewald.

Bryan notes “Historically we think of a scientist locking himself in a room and six months later emerging shouting eureka! That has obviously changed.” Now a maximum of 1.8m linear bench space is afforded per scientist and a carefully calibrated ratio of lab space against total floor area is calculated, including modern working methods such as hot benching. Recounting some stats and figures Sennewald advises that 250 researchers are employed from a working population of 464. The total net floor area is 8,000sq/m, in reality it was 7,999sq/m, “but it was easier to add the one,” Sennewald observed. The total construction cost was £43.3m.

Due to the need for biological control the government’s health and safety executive HDR were required to perform a series of leakage test. “It’s a very tight building - unless you open the windows,” Bryan noted. Of the four levels of containment defined by regulators, one representing standard school chemistry and four equating to biological warfare, Roslin has been categorised as a level two facility - the most common ranking used to define most university labs. Though a range of animals are investigated in the lab areas experimentation predominantly takes place at the genetic level using tissue samples. Nevertheless, as the bumpers attached to some lab side doors attest, in addition to the buildings human inhabitants hundreds of mice will also call the facility home. Housed in large caged trolleys and wheeled from experiment to experiment these unwitting denizens will spend much of their time in windowless chambers, complete with an interstitial floor above so that technicians can replace broken light bulbs and filters without the need to enter contaminated areas.

Project manager Marc Edmondson, assuming the role of tour guide for the day, walked through the construction process. The design was first formulated upon the occasion of the team’s first site visit when Edmondson frog marched the team up the nearby Pentlands in order to better appreciate the lie of the land. That walk ultimately inspired their eventual solution which carved two separate elements into the Midlothian countryside.

The first and most dramatic element is a glazed gull wing façade splaying at both ends along the sites southern flank to expose views of the Pentland hills and Penicuik. Overhangs and cantilevers abound in a display of structural gymnastics which surely challenged the engineers. “Aecom love working with us because we challenge them, the atriums and spaces are all at different angles,” notes Edmondson, who observed, “there was “total transparency with the contractor which I found quite uncomfortable!” Housing open plan offices this dramatic space is shaded by bris soleil shading off the areas of glass without colour, serving the dual purpose of both reducing glare and also adding rhythm to the façade, adding variety and visual interest to key areas whilst throwing subtle greens and browns (reflecting the surrounding countryside) inward in an almost “ecclesiastical” way, narrates Edmondson.

Standing in stark contrast to this cathedral of light is which provide the building with a very different character on its north and south elevations. To the south lie open plan, fully glazed offices, whilst laboratory areas area. Edmondson explained: “The façade of that area would look horribly synthetic if you used man made materials. Each panel is hand finished on site in brass to break down that area because the science doesn’t lend itself to a fully glazed façade.” Dark brown of the bronze reflects the Midlothian countryside. “It looked like an Aztec temple at first” Edmondson recalled, “I had to build a sample panel in my garden to show that over a weekend it would darken right down.”

Although rated Very Good by Breeam for its design the building this was not taken through to construction as from a cost perspective HDR decided not to take it forward. Nevertheless Edmondson remains proud of their achievements noting that “as much as possible is naturally ventilated” but windowless laboratory areas require mechanical assistance, equating to a 50/50 split in the buildings ventilation options. Such considerations extend to window blinds, a special glass coating, external sunshades and skylights that double as exhaust chimneys all designed to keep the air flowing and cool people during hot days.

At first glance the plush white leather seating in the boardrooms of the “posh” end of the building looked like a foolish decision but Edmondson explained “we went over them with pens, they wiped off a treat,” adding “turn them to the side and they self right.” It is subtle details like these, including a spray on finish on the concrete to dampen the footfall noise of people walking through along with store cupboards and monk like “study cells” built into the walls which make for an imaginative use of space. Indeed the only regret Edmondson expresses on our walk relates to the atriums “I had hoped to have the full wall glazed but that saved us £0.5m in the internal atriums.”

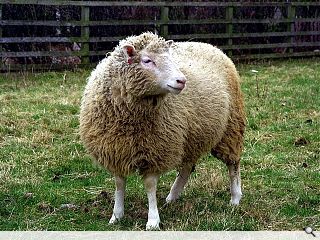

Dolly the sheep may be no more but the science which created her lives on. The Roslin Institute illustrates that just as its architecture can serve to help its scientists to lead international research into a range of animal related studies that have evolved from the cloning of sheep to the development of GM chickens which don’t transmit bird flu and strategies for combating a viral disease in Atlantic salmon.

ROSLIN INSTITUTE

Client: Bush Research Consortium EBRC: The Roslin Institute; The Scottish Agricultural College; The Moredun Research Institute; The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, University of Edinburgh

Total cost: £60 million

Completion: December 2010

Main contractor: BAM

Architects: HDR Architects

Quantity surveyor: Turner & Townsend

M&e consultant: AECOM

Structural Engineers: AECOM

Photography: Norman Russell

|

|